With the pea season almost upon us, and many children, parents, and teachers looking for a break from screens, I would like to highlight the potential topical relevance of Friedrich Froebel’s peas work, or ‘sticks united by peas’, which I came across recently in “A Practical Guide to the English Kindergarten” written by Bertha Ronge in 1854. Ronge studied under Froebel, the inventor of kindergarten (or ‘infant gardens’), before moving to Britain and opening the first English-speaking kindergartens, in Tavistock Place, London, in 1851, and a few years later in Manchester and Leeds.

For Froebel, brought up in a small village in the Thuringian forest in Germany and originally an apprentice forester, communing with nature was at the heart of education. He went on to become an assistant to a professor of crystallography in Berlin, which led to an epiphany:

The stones in my hand and under my eyes became forms of life which spoke a language I understood. The world of crystals clearly proclaimed the structure of man’s life to me and spoke of the real life of his world. (Froebel 1967, p.39)

This revelation made sense of the child’s love of playing with building blocks:

in his [sic] own development he follows the course of Nature and imitates her [sic] modes of creation in his games. He likes to build and to imitate the structuring of form which we find in Nature’s first activity, in the formation of crystals. (p.38)

Wooden building blocks became central to Froebel’s set of six ‘Gifts’ to support children’s play in kindergarten, spawning a legacy of blocks as toys which continues in Lego, Minecraft and Roblox today. Famously several key 20th century architects, including Le Corbusier, Buckminster Fuller and Frank Lloyd Wright were brought up with Froebel’s blocks and acknowledged their influence on their designs and so, arguably, much of the modern built environment.

As children grow older and more dextrous Froebel also recommended ‘occupations’ – crafts such as weaving, painting, paper-folding and ‘peas work’, which involved building crystalline and other structures by using peas to join the points of thin wooden sticks, similar to cocktail sticks. Buckminster Fuller – famous for designing geodesic domes – recounted his experience at a Froebelian kindergarten in New England around 1900:

One of my first days at kindergarten the teacher brought us some toothpicks and semi-dried peas, and told us to make structures. With my bad sight, I was used to seeing only bulks. I had no feeling at all about structural lines. The other children, who had good eyes, were familiar with houses and barns. Because I couldn’t see, I naturally had recourse to my other senses. When the teacher told us to make structures, I tried to make something that would work. Pushing and then pulling, I found that the triangle held its shape when nothing else did. The other children made rectangular structures that seemed to stand up because the peas held them in shape. The teacher called all the other teachers in primary school to take a look at this triangular structure. I remember being surprised that they were surprised. (Quoted in Brosterman p.84)

In a curious loop back to crystals, when researchers discovered polyhedral structures of carbon atoms in the 1980s they named them ‘fullerenes’ after Buckminster Fuller’s architectural designs.

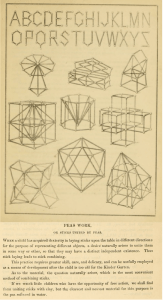

During lockdown I attempted some peas work with my 10-year old niece who I was bubbled with (results pictured below). Apart from their biodegradability, and the fact you can eat any left over, one satisfying aspect of peas is that they set hard overnight giving the structures some permanence. The main tip I would pass on is that garden peas – fresh, soaked from dry, or defrosted from frozen – are better than petit pois, or tinned marrowfat peas, which both tended to disintegrate on being pierced. Sweetcorn, hard berries and other veg would probably also be suitable, or whatever is in season outside.

Having struggled to read some Froebel in English translation, for me Bertha Ronge’s book was a better contemporary introduction to his ideas. Clearly a labour of love, it is written in beautifully crisp Victorian English, with painstakingly hand-drawn illustrations – complete with endearing mistakes (see eg the alphabet in the picture, top) – and some unexpectedly fresh-sounding insights on the psychology of child development, such as babies’ attachment to caregivers, years before Freud was born. It also communicates a philosophical relationship with nature which seems to resonate with 21st century new materialists such as Jane Bennett, who in Vibrant Matter (2010) echoes Froebel’s sentiment on sensing life in objects in her environment she previously thought of as inert: “I caught a glimpse of an energetic vitality inside each of these things, things that I generally conceived as inert” (p.5).

Recently I was glad to notice some teachers keeping the tradition alive on Twitter, at #SticksAndPeas.

Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant matter: A political ecology of things. Duke University Press.

Brosterman, N. (1997). Inventing kindergarten. Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

Froebel, F. (1967) in Lilley, I. M. Friedrich Froebel: A selection from his writings. Cambridge University Press.

Ronge, J., & Ronge, B. (1854). A practical guide to the English Kindergarten.

Blogpost written by Michael Rumbelow